44 Duos for Two Violins, sz. 98

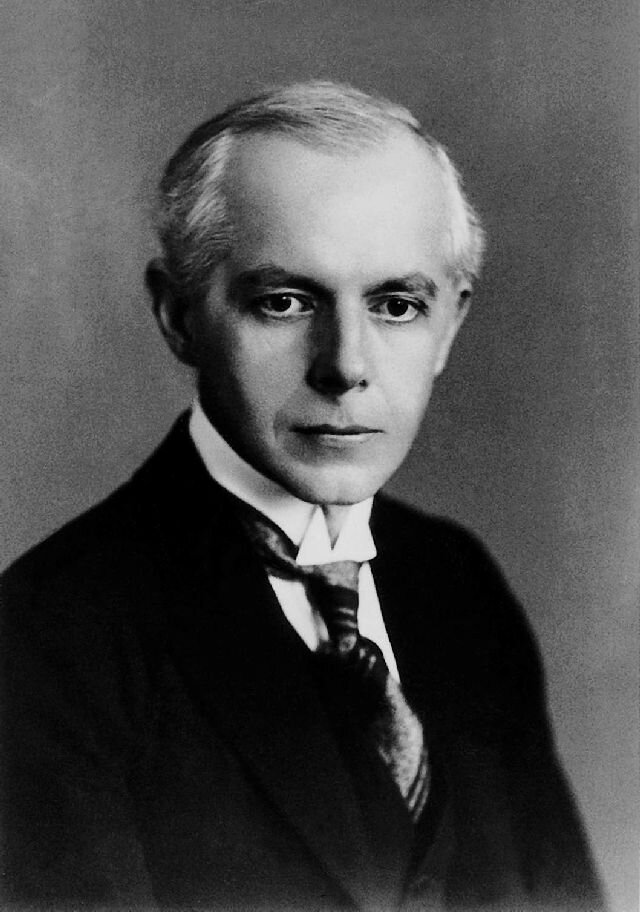

Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945)

Béla Bartók was a pianist, one of Hungary’s most famous composers to date, and a founder of ethnomusicology.

Bartók’s mother claimed he could differentiate different dance rhythms before he could speak full sentences. This fascination with musical structure continued through his early years, and at eleven he performed his first public recital, which included one of his own compositions. His career found its trajectory at twenty-three, when he overheard a folk tune sung by a Transylvanian nanny to the children in her care. This launched his life-long search and obsession with Hungarian and other folk music, which frequently use complex meters and modal scales. He traveled across Europe recording these tunes, and then incorporated the melodies faithfully into his own intricate compositions.

The three violin duos on the program today are from a collection of forty-four that Bartók wrote at the request of Erich Doflein, a German violinist and pedagogue. Doflein wanted Bartók to arrange some of the piano pieces from Bartók’s book For Children, a collection of eighty-five short pieces written for students based off Hungarian and Slavic folk tunes. Doflein and his wife were hoping to start their own violin method for students, but felt there weren’t enough student pieces with artistic merit.

Instead of simply arranging his piano pieces, Bartók composed forty-three new pieces for two violins, arranging only one of the piano works. These pieces covered more geographic territory than those for piano, using not only Hungarian and Slavic tunes, but also Romanian, Serbian, Ruthenian and Arabian songs as well.

Bartók divided this collection into four books of increasing difficulty. The first of these pieces on the program, Hay Song, is the twelfth song from the first and least-advanced book, although it is already the second that uses polytonality, meaning to play in more than one key simultaneously. The last two pieces on the program, Pizzicato and Arabian Dance, are from the most advanced book. Pizzicato is written entirely for plucking the instrument in place of the bow. It jumps between single notes, chords and double-stops (two notes at once) while outlining simple melodies, a difficult challenge for coordination and rhythm. Arabian Dance provides an exercise in syncopation and a variety of bow techniques.

The progression of these books may indicate Bartók’s purpose in writing them. Almost immediately, students are introduced not just to technical virtuosity, but also to harmony, complicated meter, and modernism. They take children on anthropological tours of national folk music, music Bartók was careful to preserve—strictly removing songs from the For Children collection he discovered were not accurately transcribed or were not original folk tunes.

Bartók’s motivation becomes clearer through the work of his contemporaries. While few composers of Bartók’s fame devoted as much time to writing music for students, he was not the only Hungarian involved in this endeavor. Kodály, his friend and colleague, was also blending folk music with art music. Kodály explained that “our task [as modern composers] can be summarized in one word: education.” He hoped to “drive the Hungarian masses closer to higher art music” at a time when art music was veering away from tonality, and harmony was becoming so complex as to lose its approachability. So, although Bartók’s 44 Duos for Two Violins were never meant for formal performance, they were likely intended to be a gateway for both performer and listener into his new world of harmonic and rhythmic complexity, a different kind of virtuosity—a virtuosity not only in the hands, but also the ear.